March 19 - Today's post contributed by Kerrie Logan Hollihan

When I was in AP American history class at North Allegheny High School a long time ago, the guy who sat in front of me mentioned a couple lines in our textbook that showed up on one of our tests. “The Grimkee sisters?” he said, shaking his head as if to say “Who could possibly care?”

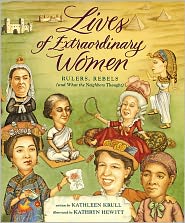

Later I did -- much later. Fast forward 40+ years, when I wrote about them in my book Rightfully Ours: How Women Won the Vote, which appears this year on the ALA Amelia Bloomer List. The sisters, Angelina and Sarah Grimké, daughters of a Southern judge and slave owner, hated the idea that anyone, including their father, could own other human beings.

First Sarah, and later Angelina, took the drastic step of leaving home and moving north to Philadelphia. There they became Quaker women, free to speak openly during worship. The Southern sisters then took things further and went on tour to speak about abolition in public meetings. At this point, even their fellow Quakers frowned when the Grimké sisters spoke in public. Other women -- Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone especially, also found their voices as abolitionists and only later began to work for women’s right to vote.

Rightfully Ours covers the lives of many American women -- some well-known, such as Anthony; others not quite as much: Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Alice Paul; Carrie Chapman Catt and “footnotes” like the Grimké sisters. I was grateful when my editor suggested I write a history of the American suffrage movement -- CRP was looking for a book on the topic.

My previous book, Elizabeth I: the People’s Queen: Her Life & Times had taken me back to Tudor England, researching and writing the life of one, very strong woman who came to power almost by accident. This time, there was a host of women to study, and by the time I was ready to start writing, I’d read parts of at least 60 books just to feel familiar with these women and the world they inhabited.

Rightfully Ours is my fourth book with Chicago Review Press, and what makes these “For Kids” books a bit different is that we authors must develop at least 21 themed activities to enhance what we write. Hence the “21 Activities” you’ll see on the cover of most of CRP’s broad-ranging series of books for middle grade readers. We develop these to appeal to a broad audience -- and I blog with my fellow “for Kids” authors Mary Kay Carson and Brandon Marie Miller at Hands-on-Books, where we talk about our books and offer downloadable activities. (http://hands-on-books.blogspot.com)

In my books I like to include a few activities with a scientific touch. For Rightfully Ours there are several -- one on how to locate Polaris (the North Star), and another, Make a Five-Pointed Star with Just One Cut.

Today I’m sharing a favorite of mine. In their early days, women like Anthony, Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the Grimké sisters read by the light of whale oil lamps. I fashioned an activity for Rightfully Ours so that my readers can make lamps of their own using not whale oil of course, but olive oil. It’s easy to make one using things you can find around the house and in craft stores -- and these little lamps really do work!

Kerrie Logan Hollihan writes award-winning nonfiction for young people. Her books have been honored by the ALA’s Amelia Bloomer List, Smithsonian magazine, the National Science Teachers Association, the Chicago Public Library, and the Junior Library Guild.

Hollihan channeled her “inner sixth grade girl who read Compton’s encyclopedia for fun” and started writing for kids in 2005. She’s the author of 38,000 word biography/activity books about Isaac Newton, Theodore Roosevelt, Queen Elizabeth I, and the women’s suffrage movement in the U.S., as well as an early reader series on Latin American celebrations. Either way, Hollihan says, every word counts.

“Kids don’t get enough credit for being able to understand history as it actually happened. As I research and write, I think about how to explain the ‘whys’ of situations as well as the ‘whats.’

“History is filled with great yet fully human men and women with faults and foibles. When I write about famous people and their times, there are tough issues to address -- segregated America and religious persecution in England are topics I’ve explained to my readers.”

Hollihan, mother of two grown children, lives with her pilot husband Bill in Blue Ash, Ohio.